FAN ART

As The Cultural Logic of The "Ghibli-style" AI Trend

Here’s a thought experiment: What would happen if several generations of people were conditioned to have fan cultures and brand loyalty as a core part of their personality and then were given a tool that could instantly turn any picture of themself into the style of their favorite fandom?

Cognitive dissonance is the societal norm in the 2020s. It’s the only way to get through the daily routine of opening your phone to see “new horrors beyond comprehension” and pictures of your friend’s newborn baby in the span of two seconds. Magnify this by twenty-four hours, and you get what is commonly known as doomscrolling. This reality has created a cynical and removed social engagement. It’s easier to be ironic than to engage sincerely with the onslaught of chaos around the planet. Besides, it’s just the internet, right? It’s all just a joke, right? Art critic Ben Davis recently coined the term “delightmare” to describe this cultural milieu.

But, sometimes the delightmare speaks to something very real about the culture we live in. An uncomfortable truth is revealed through the absurdity. Cognitive dissonance intensifies.

The Ghibli-Style AI

Like most people who spend any portion of their day online, I was met with a flood of Studio Ghibli-style images on my feed this past Wednesday. As I scrolled through them, I received a text from a friend. She had sent a few images depicting her and her partner as Ghibli-esque characters. I figured it was a trending AI filter app, but it turns out it was the newest update from ChatGPT. Before I could catch up on the trend, the hot takes began to roll in. Condemnations of OpenAI for stealing copyrighted Ghibli artwork, takedowns of “lazy” people for using the tool, and woke scolding about the environmental impact of AI tools. You name it, and a person was screaming about it online. For me, it all ended with the shocking Ghibli-fied image the White House official Instagram account posted that showed an ICE agent detaining someone for deportation. The delight had officially transitioned into nightmare, and suddenly, it all felt very distasteful. Time to (doom)scroll to something else.

For the rest of the week, hot takes and outrage about the Ghibli-style AI have dominated online discourse. The internet was abuzz while the OpenAI GPUs were melting. All thanks to the beloved Studio Ghibli. But what exactly are people upset about? To me, there seems to be a dissonance between the outrage over the trend and the status quo of cultural production in the 21st Century.

Fandoms and Extended Universes

The outcome of my thought experiment is the moment we’re living in. It’s the internalization of a political imaginary that's only forecasting is There Is No Alternative to the current status quo. When there is no alternative, then there is no change, hence an ever-present that can only reproduce what has already existed. This is why Disney’s business model is to expand sideways and never forward into new ideas. It’s why every major studio won’t take a chance on a lower-budget new idea but will fund another Marvel movie. The mix of this economic logic and “the daily horrors” has created a culture of nostalgia and pastiche. In other words, fan culture.

This theory of culture is well-trodden by theorists, academics, YouTubers, and posters alike, with Adorno and Horkheimer’s famous 1947 essay The Culture Industry and Frederick Jameson's 1989 book Post Modernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism serving as major theoretical foundations. In the 2010s, it was repopularized by the late Mark Fisher through his book Capitalist Realism. Despite its almost retro flavor, the Capitalist Realism hat still fits. Somehow, in 2025, Disney is still pushing live-action remakes of its iconic IP, biopics of once-famous musicians are still winning awards, 90s reboots aren’t slowing down, and the popularity of cinematic universes like Marvel and Harry Potter is still thriving.

The foregrounding of IP and brand by major companies to bolster sales while they largely failed to create anything new for the last 20 years has imprinted onto the culture in the form of intense fandoms. Don’t even think about dissing Taylor Swift or her fans will doxx you and get you fired, etc. The once niche areas of fan culture like comic, game, and anime conventions and even cosplaying are now firmly popular culture. All of this is bolstered by merchandising. The wall of FunkPops or 90s cartoon ephemera is a cliché now. Within a social fabric that is deeply frayed and polarized, people are clinging to the shared love and lore of their media of choice. This para-social connection stands in for traditional social and community connections that just don’t exist anymore.

Of course, just because these trends don’t resemble a mythic “better” past doesn’t mean they are bad developments. The generation-spanning fan cultures are a way for families to connect, for example. The aging Spiderman fan can introduce the character to his young child, and they can both enjoy the next Marvel movie together. This era has also given rise to a resurgence of genre filmmaking with a particular soft spot for horror, perfected by studios like A24. Broadly speaking, the past several decades can be viewed as the triumph of once-marginalized media cultures over popular culture. But by the end of the aughts, fan culture seemed to reach a tipping point. By 2020, Trump fanatics were cosplaying as Captain America while storming the capital, police were openly identifying as The Punisher while brutalizing protesters, Disney Adults were risking their families’ lives during a global pandemic, and Swifties had more power than traditional political parties.

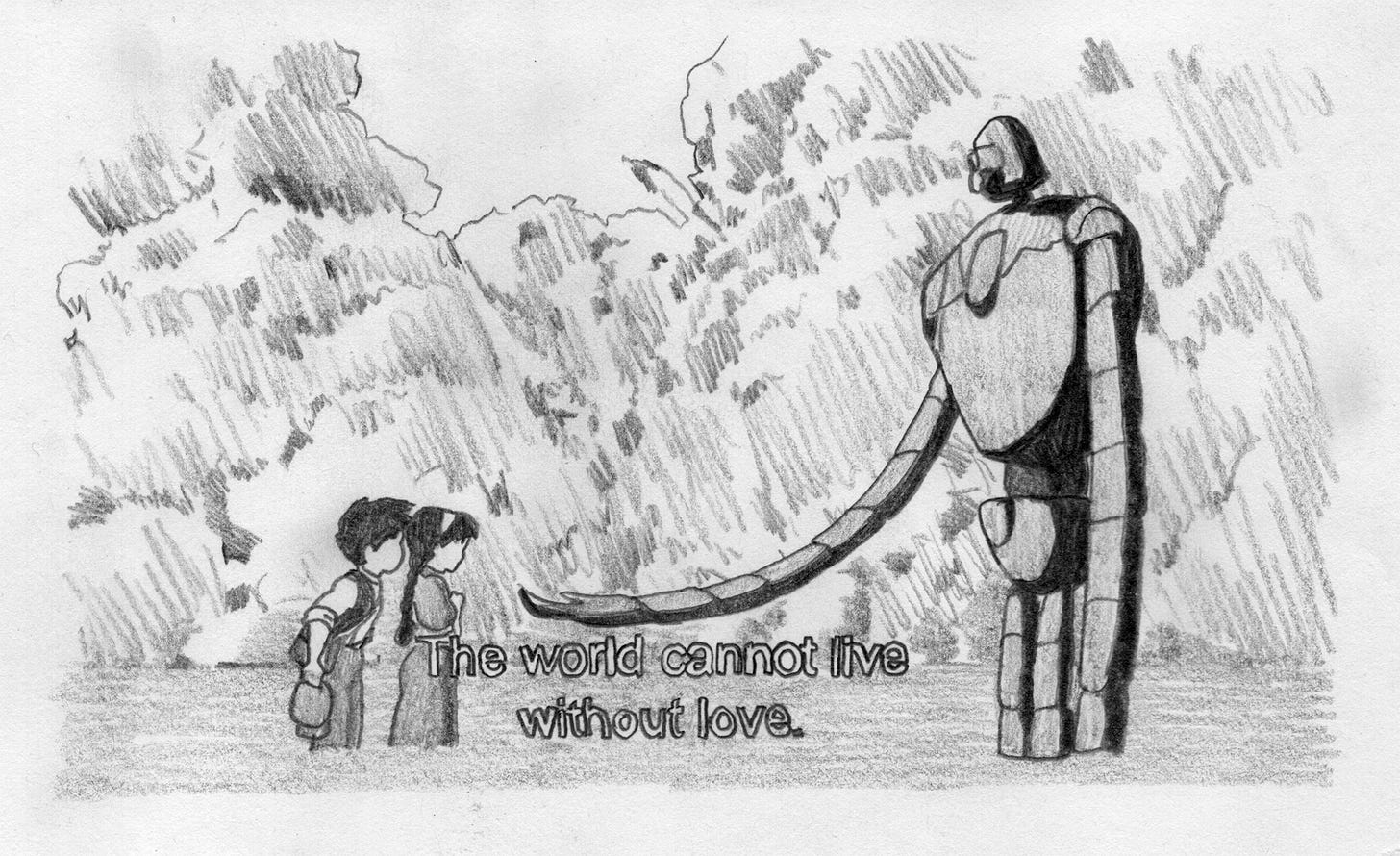

It seems that the entrenchment of reboot, sequel, and extended universe media has spawned a rabid fandom culture. Add generational downward mobility, rising costs of living, poor job placement, and a global pandemic to that, and you get a bad situation. When the present and future are full of delightmares, daily horrors, and doomscrolling, it’s comforting to escape to a known world with defined rules and logic. When culture does not offer new visions, and when society is not able to provide a positive outlook of the future, then people look backward. But, people are products of the systems they live in. And, this system is built on incentivizing chaotic fandom because it drives sales. Creativity and novelty are not part of the equation. Miyazaki himself has criticized the negative influence of overbearing fan culture on the Japanese animation industry, famously saying, “those who identify as “otaku”, they sicken me deeply.” Is it such a surprise, then, that the newest innovation in media production is a tool that can essentially only look backward? Isn’t it actually the exact type of tool that a culture obsessed with reproducing the same IP would create?

The Millenial Creative as Fan Artist for Capital

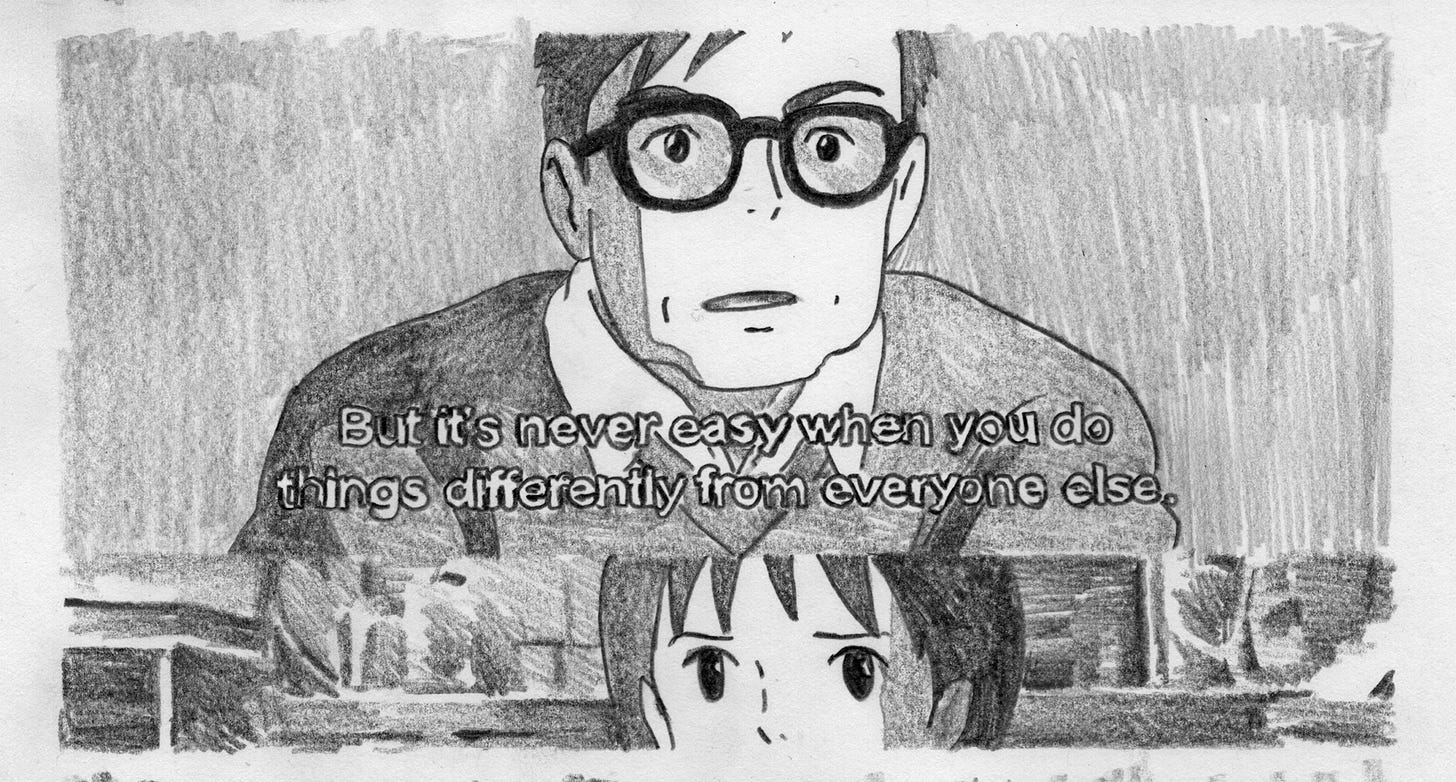

The backlash against AI tools, and generative AI in particular, seems to be the strongest from the Millenial creative class. Belonging to this class myself, I can understand the anxiety of watching the birth of Machine Learning tools that can do the work you spent your twenties going into a lifetime’s worth of student debt to learn in less than one minute. My generation cut its teeth on the gig economy and building personal brands on each new social media platform that launched. As the shine wore off for us from the “freedom through freelance” mindset and the realities of isolated, inconsistent work with zero worker protections set in, the precarity of our situation became glaringly obvious. Add aging into our mid-30s and early-40s to the equation, and you get people sublimely freaked out by AI tools threatening their livelihoods and worse, their personal brands.

There is something unspoken lurking in the background of the most impassioned critiques of generative AI. Between the cries of plagiarism and unoriginal lazy mimicry is the fact that there is almost nothing original or unique about culture now in the first place. Putting aside the dangerous and ahistorical simplification of creativity as originality, the implication that the majority of the artists whose work has been used in part to train generative AI models was completely unique and devoid of reference, homage, or stylistic lineage is just fantasy. The reality is that due to neoliberal economic pressures and platform reward incentives, many millennial creatives’ portfolios were, from the start, flattened into easily digestible and algorithmically popular art styles. The most pervasive instance of this was the “Corporate Memphis” flat illustration style that every designer/illustrator and major brand simultaneously adopted around 2020.1

The entirety of the millennial creative class can’t be written off this way, of course. Navigating the algorithmic platforms became an art practice in its own right. Artists like Molly Soda and collectives like DIS or The Jogging positioned their art practices around a self-awareness of the online-centric millennial creative boom. Their work fits into a loose category of art from this period called post-internet art. Other artistic sub-genres enjoyed pockets of success during this time, like the indie and experimental animation renaissance on Vimeo, and the indie games boom supported by platforms like Kickstarter. Each of these examples worked because they weren’t easily marketable, at first anyway. By the end of the aughts, the once novel stylistic trends of these pioneers had been ingested into the millennial brand machine, and with Covid, most of these booms had officially ended.

Being raised in a culture stagnating in its own obsession with copyright and IP, we millennial creatives were foisted into the Wild West of platform capitalism. By the mid-2010s, it became common practice for companies to cross-reference social media stats before hiring someone. Naturally, an incestuous relationship formed, and the millennial creatives’ portfolio began to resemble the work already being done at the company they wanted to work for, which was a company that was devoted to reproducing its iconic brand ad infinitum. Through those pressures, we pioneered the personal brand platform economy. The thing we didn’t understand was that by optimizing our creative output toward the companies we wanted jobs from, we were actually attuning ourselves to the algorithmic logic of both the platforms and the companies themselves. In the end, millennial creativity was much more about finding ways to stand out in the mass of other people whose products looked almost identical to theirs. To use a meme, maybe the real creativity was how we gamed the system along the way.

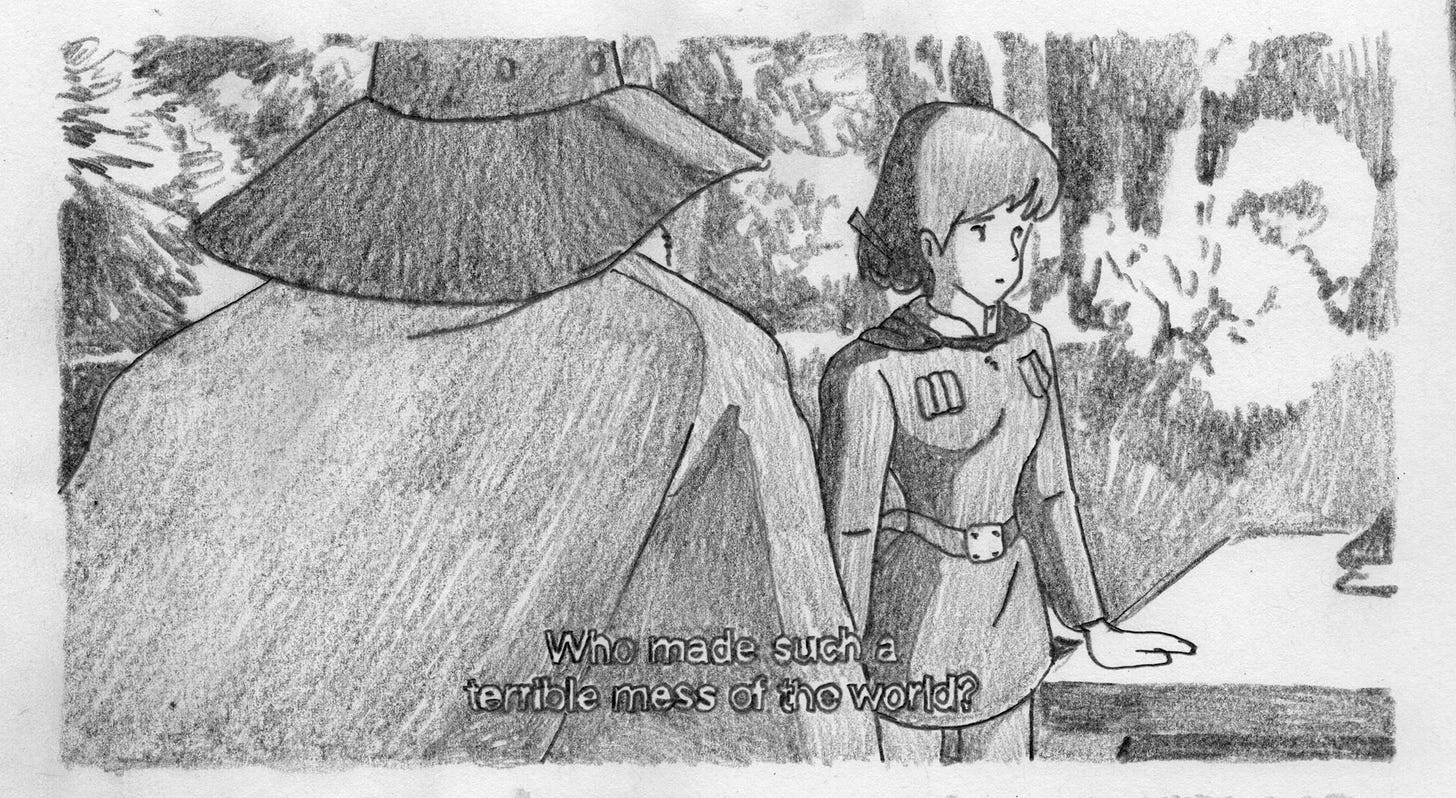

From Fan Art to Opp Art

Technology theorist Benjamin Bratton uses the phrase The Inverse Uncanny Valley to describe the weird and sometimes unsettling experience that users of AI systems report having when they see themselves mirrored back by an AI. Met with a reflection of ourselves through non-human “eyes”, it’s like we don’t believe what we’re seeing is actually us. I think this is exactly what the internet experienced last week when the Ghibli AI trend exploded online. Seeing our iconic meme photos translated into a beloved art style created a profound unease and dissonance. We were met with the very cultural logic that we’ve been participating in for most of our lives, and it left a bad taste in our mouths. It felt fake, empty, cheap. It paled in comparison to the real thing. Isn’t this the hardest truth of 21st-century cultural production anyway? Isn’t it what we all already know about the “slop” era of algorithmically optimized media? That it is boring and uninspired. Miyazaki himself has weighed in on these aspects of contemporary culture and AI. Bratton asks us to consider if this type of realization is “the point” of AI, if this type of shock can actually teach us something and, hopefully, change the culture for the better.

So, should we really be surprised that the machine learning algorithm built by fanart-era humans and trained on fanart-era artwork is being used by fanart-obsessed humans to create fanart? No. But, maybe the answer is not to smash the mirror that showed you something about yourself that you didn’t like. Even if you did, you’d still have to reckon with what you saw in the first place. It seems like a better use of our time is to find ways to reject the never-ending march of expanding fandom content and to use the new tools in a way that opposes the cultural logic of the pre-generative AI era.

What would an Opp Art culture look like? I think it would look something like the artistic practice of Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst. They have spent over a decade developing artworks, having conversations, and writing about consent, ownership, and authorship in a post-AI world. They aren’t Doomers, and they also aren’t naive. As artists coming up in the fanart milieu I described above, they have serious criticisms of the incentive structures that hurt their field of music production, and they accept the possibility of that compounding in the generative AI era. But, they also accept the moment we’re in, and rather than run from it, they have chosen to critically engage with it. They view our historical moment as an OPPortunity to create new models for a future that is currently unfolding before us.

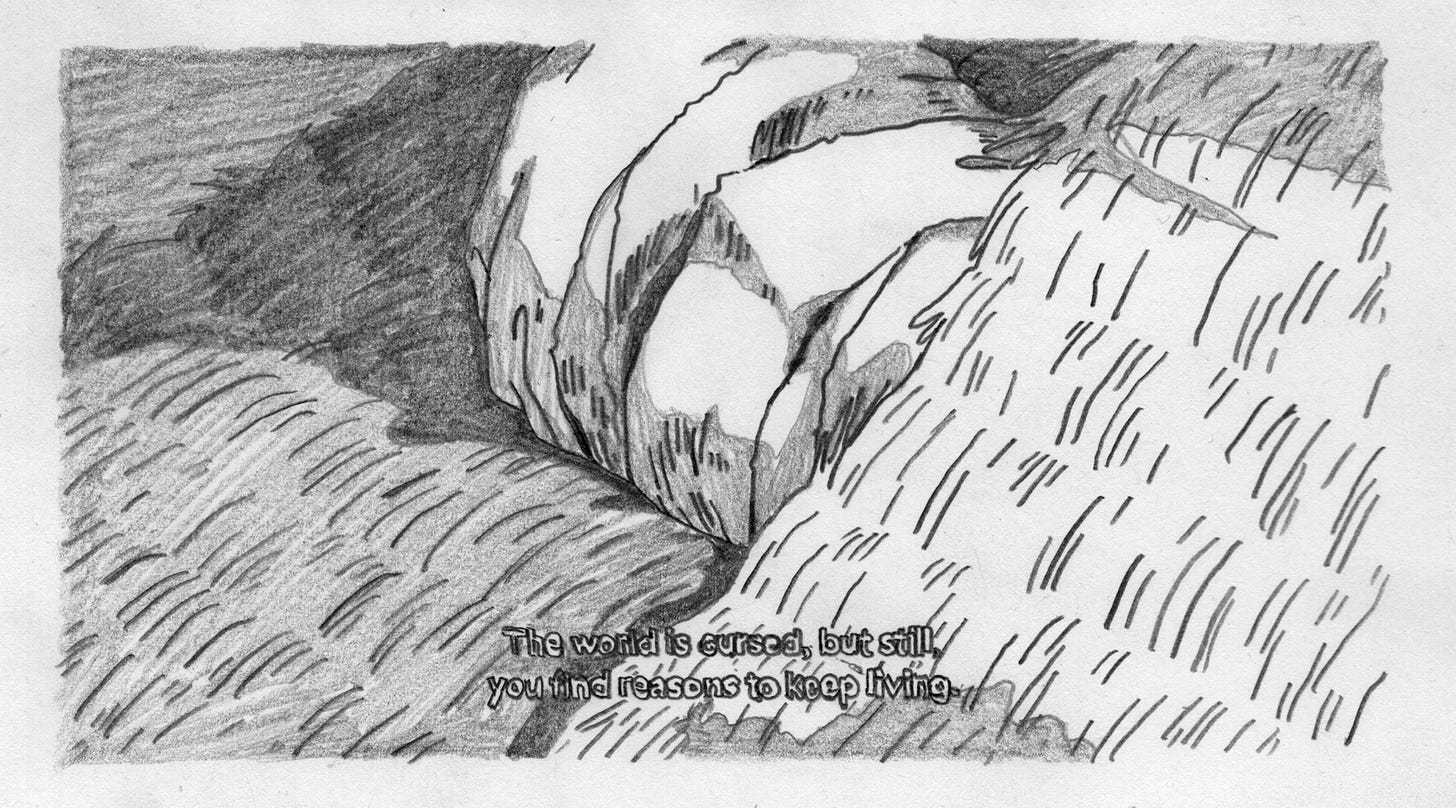

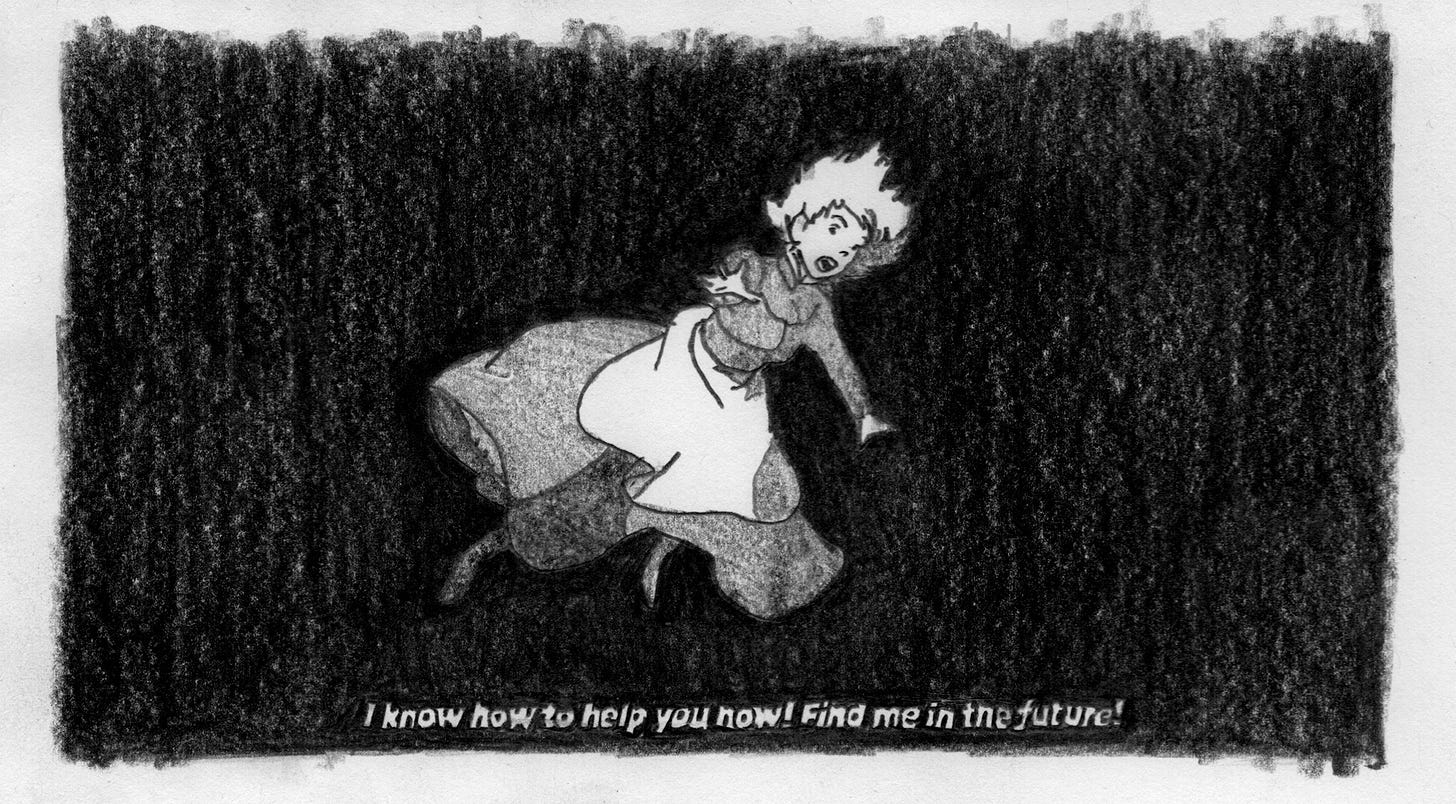

Many of my friends who teach art at the college level tell me their struggles in combatting fan art. Their students have grown up in a culture that celebrates this type of engagement with art, and it’s very hard for them to think outside of it. Faced with tools that can exacerbate this tendency for mimicry, it feels more important than ever to oppose this culture. But, an Opp Art culture is not one that wishes to return to the pre-generative AI era because that is the era that got us here. It is instead one that rejects the cultural logic of Fan Art in favor of one that encourages experimentation, collaboration, and critical engagement with new tools. It is also one that engages with the best and worst of the complex web of AI development and the intricate political machinations that created it. Artists like Trevor Paglen and researcher Kate Crawford both come to mind. The worst of any new artistic medium is always when it’s used to recreate the preceding artistic style. The camera had to grow out of its panorama phase before it could be accepted as a true art form with unique characteristics. Cinema had to do the same. Certainly, AI art tools can and will have a similar trajectory. This isn’t to say that people should stop making art without AI tools, I myself will never give up graphite drawing. But I want to live in a culture that can move beyond zombie art styles and entrenched fandom aesthetics. Even more than that, I want to live in a culture that can imagine a different future, because the one that’s unfolding around us is pretty horrific, but many people seem content to just keep watching the reruns. I say we must let the shock of the inverse uncanny valley propel us into a new future.

A previous version of this article used a term that has negative connotations to the LGBTQ+ community. After being made aware of the history of the term, I chose to remove it from the piece.

What a thoughtful article. I have often wanted to open a conversation between AI and my own work, but am hesitant to jump in because of possibly losing track of my own body of work. It seems such a promising creative tool if you don't let it disguise original thought. And that leads to questions about how original is any thought? Your point about No Future is a good one, always limited to the past. but your point about new media needing to practice old ways before it can extend an art form out to include new territory is an excellent point. Thanks!