Toward A Rotoscopic View of Society

All of us, and our images, have been rotoscoped

What Kind of Image is This?

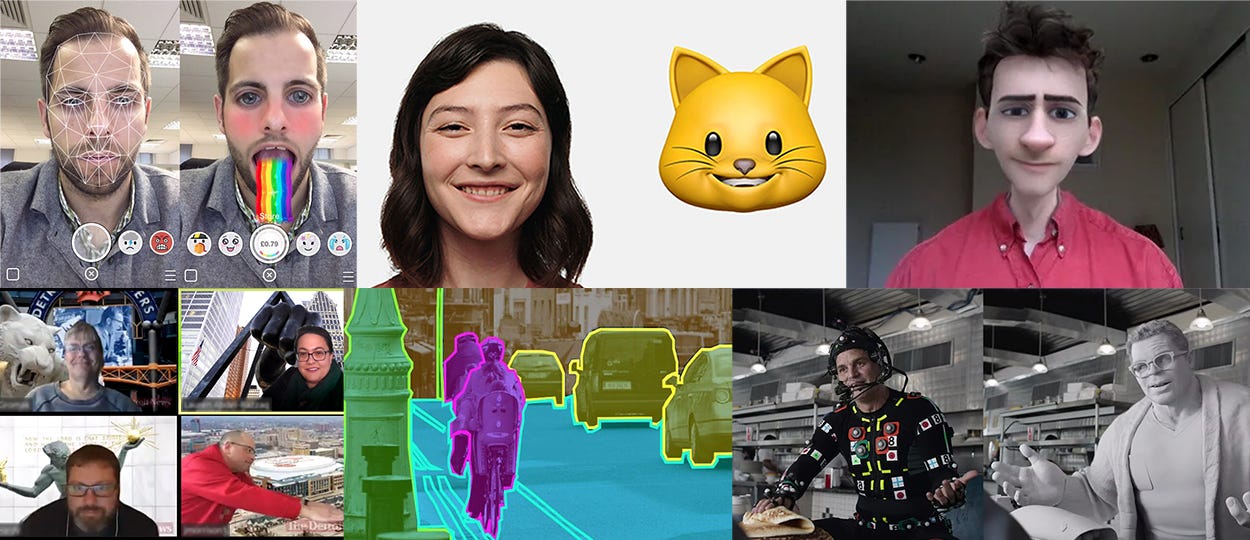

The influx of AI-generated images circulating online and the debates happening for and against them have overshadowed the persistence of another type of image that dominates the media landscape today. This image is a selfie face filter, a deep fake, an augmented reality app, computer vision-aided object detection software, or the MoCap data-infused CG character in a superhero movie. In this image, the subject exists between layers as a composite-able element that can be easily merged with other images and whose states of movement are tracked for image mapping. Contemporary discourse struggles to settle on a name for such images, frequently relying on terms like “digital” which do little to describe how they are actually created and often lead to a misunderstanding of their historical emergence.

Setting aside their digitalness, we can understand these images as having two parts. First, they are composed of several image assets. Second, they incorporate the movement of the subject of the image. As such, they stem from the long history of special effects images that have quietly supported both live-action and animated cinema for the last century. It’s within this milieu that a useful term arises for describing the new images of our day. That term is rotoscopic, and it takes its name from the often derided but extremely common technique called rotoscoping. Rotoscoping is a frame-by-frame image manipulation process invented in the early 20th Century. It was used by film and animation studios to add cartoon characters over recorded human movement and to create masks and mattes for footage compositing. It developed alongside other special effects techniques, each performing the same function: the removal or isolation of a subject through tracking for the purposes of compositing or embellishment.

Rotoscopic neatly describes the current image regime, while pointing directly to the historical moment in which such practices had their beginnings. It is not meant to rewrite or obscure other similar practices that don’t full under the specific rotoscope process as it is understood in film and animation production. Instead, it intends to provide a framework, or an ontology, for describing our contemporary visual culture. The dominant modes of image discourse, that of photographic or cinematic images can no longer contain the new images. In their place, the rotoscopic image has taken hold. To recognize the scope of the rotoscopic era, it’s important to understand the history of the rotoscope technique, what exactly it does, how its images differ from others, and finally the effect of its ubiquity on culture in the form of a gaze.

The Rotoscope Technique

As a technology, the rotoscope does two things. First, it removes a subject from its context or background. Traditionally, this was done by tracing, cutting, or painting a subject out of a sequence of images frame-by-frame. At first, a human was needed for this step but today it’s done with relative ease by algorithmic computation and computer vision. The byproduct of this step leads to its second usage, the creation of movement data. Once removed from context, what is left, regardless of content, are states of motion. Therefore, rotoscope is a technology that produces an index of movement in time. At first, this took the form of silhouettes of actors but is now increasingly rendered as mappable data points. In both iterations, its primary usage is to map new images on top of captured movement data. Despite being aesthetically divergent, this is apparent in early rotoscoped American cartoons and digital face filters alike.

The first true rotoscope apparatus was created by animation pioneer Max Fleischer in 1915. Seeing the laborious process of animation that produced rigid cartoon motion, he devised a way to produce smooth animation based on human movement. His method was to record an actor with a motion picture camera and then trace those images onto paper one frame at a time. He built a device that pointed a film projector at the backside of a pane of glass for this purpose and patented his idea in 1917. The technique allowed him to draw his cartoon characters over recorded human action, and the process became known as rotoscoping, though it wasn’t called that in the patent. It quickly set the Fleischer studio apart because of the life-like movement it produced, with the famous Koko The Clown dance sequence from Betty Boop in Snow White (1933) still circulating widely online. After the patent period ended, the technique was used by nearly every major animation studio in some capacity, most notably aiding in Walt Disney’s turn toward realism in animation.

Rotoscoping was pivotal in the development of the special effects industry as well. Working frame-by-frame, rotoscope artists were able to embellish footage, manually cut actors or elements out of shots, and superimpose them onto another aided by rephotography, and optical printing techniques. Famous examples include the seagull attacks in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) and the lightsabers in the original Star Wars trilogy. Many in-camera tricks and film processing techniques were developed to produce this effect without frame-by-frame rotoscoping, such as matte painting, and chroma keying, or what is commonly known as blue or green screen. Despite this, Rotoscope artists were and continue to be an invaluable component in the compositing and editing process. They represent the basic manual element in an increasingly automated rotoscope process, one that incorporates techniques such as traveling mattes, and green screen, and points directly to today’s ubiquitous usage of automatic background removal and motion capture technology.

In the current visual culture, it’s hard to find a piece of media that hasn’t been touched by a rotoscope process. Superhero VFX blockbusters, virtual zoom backgrounds, face filters, deep fakes, AR/VR apps, and computer vision all combine manual and automated rotoscope technology to analyze and produce images. These far-ranging applications tend to diffuse their prevalence across the field of media production. Regardless of the content, the intended output and process employed to produce that output are the same and share the common technology of the rotoscope. That is — tracing images to isolate elements which in turn produce movement data, often with the goal of mapping a new image to that data. Understanding the prevalence of rotoscope techniques in use since the inception of film as a medium helps one to recognize the images it produces as separate from a purely photographic or cinematic image.

The Rotoscopic Image

Rotoscopic images are content-agnostic, and can therefore take many forms. If the rotoscope is a technology that separates elements from source imagery and in so doing extracts movement data from that footage, then rotoscopic images are byproducts of a manual or automated rotoscope process. In traditional animation, the rotoscopic image is a cartoon character traced over human movement. In cinema, it is the superimposed visual effect. In a smart device, it is the face filter mapped on top of a video feed. In computer vision, it is the overlaid silhouette on a live video feed used for object detection. In each case, an image has been passed through a rotoscope process to separate elements from it, and from those elements, movement data is created.

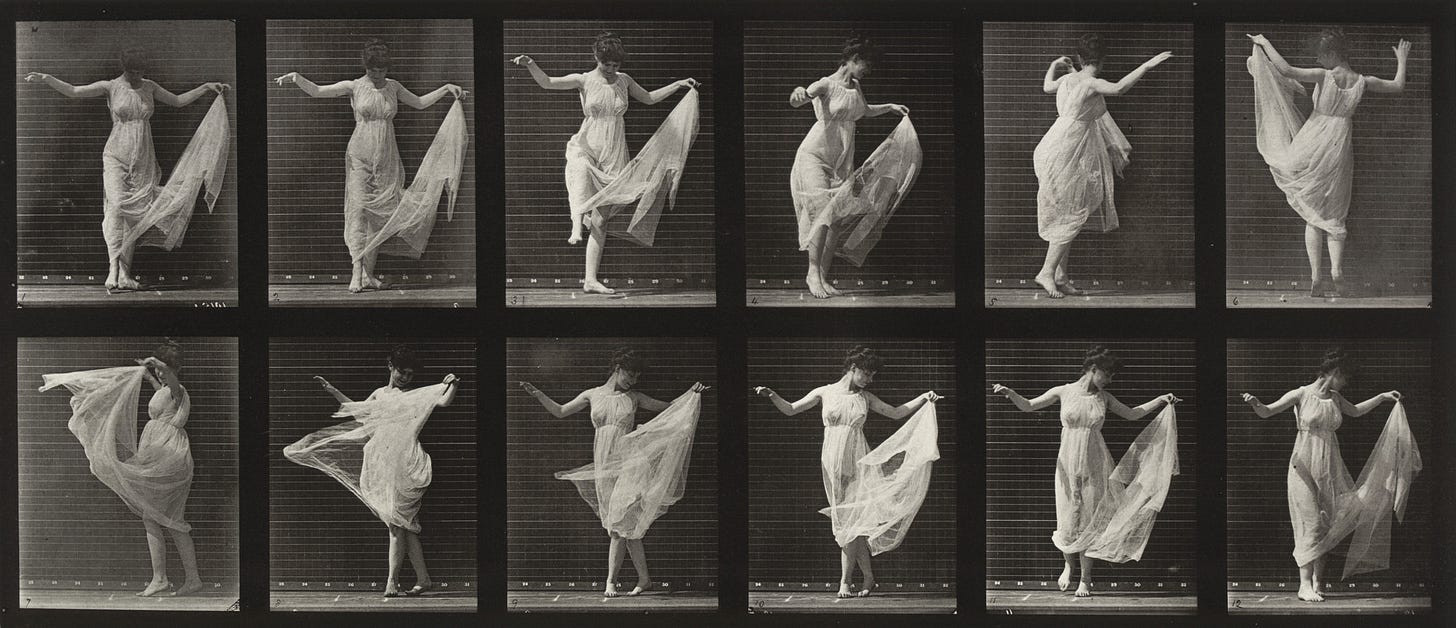

For much of the 20th Century, motion picture footage was manipulated post-photographically to produce rotoscopic images. Technicians worked frame-by-frame to manually cut out or trace over subjects from sequences of images. However, in the case of 19th Century motion studies pioneers Eadward Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Marey, this was done automatically in the framing of the subject itself. The photographers visually isolated their subjects by setting them against gridded black backdrops. The result is a ready-made silhouette; a constructed image depicting incremental human and animal movement free from context. The backdrop, acting as a proto-alpha channel, is likely the first instance of the infamous .png or .gif checkered transparency grid. These images are rotoscopic because they depict the visual effect of figure isolation while also automatically producing movement data. Regardless of the subject being photographed, it is this development that is significant. It shows that where a purely photographic image produces a document, a rotoscopic image produces data.

Furthermore, prefiguring the Fleischer method, Muybridge would have his assistants trace his image sequences onto glass discs for projection in his zoopraxiscope device, a manual example of the rotoscope technique. Famously, he used these rotoscopic image datasets to prove that a horse does indeed lift all four legs off the ground at once while galloping. In the case of Marey, his image composites reduce the figure to a state of near-total data abstraction, and in so doing resemble the data captured by digital motion capture devices used extensively in the VFX industry today. It is not surprising then that he invented the first motion capture suit to help produce his images. The troves of motion studies that both photographers created form an archive of movement data, a precursor to the motion capture libraries of stock 3D animation sites like Mixamo today.

Following these milestones, the use of rotoscopic imaging is clear to see throughout each development in film and media history. By the late 1890s, pioneering filmmaker Georges Méliès began using a black backdrop as a way to isolate characters on the film strip so he could superimpose them onto other parts of the frame. This process clearly stems from the techniques of Muybridge and Marey and prefigures the greenscreen, which as discussed earlier can be understood as an automated rotoscope process. A decade later, in the first years of the 1900s, animators began tracing their cartoon characters onto clear acetate known as “cel” to turn them into easily composite-able media assets. This freed them up from having to redraw the background on each frame and allowed for many layers to be combined to create a single image. Then only a few years later in the early 1910s, Fleischer invented his rear-projection rotoscope device, cementing the process into film production forever.

Today, what once required technical knowledge of film equipment and a considerable amount of time is now done seamlessly by smartphones and computer vision. Something that required a team of animators toiling frame-by-frame can now be done live while video chatting with friends. The software on smartphones rotoscopes users in real-time, isolating their silhouette, and replacing their background with a .jpg or .mp4 while tracking and mapping a new image over their face. This is the dream of rotoscope now fully automated and in the palm of one’s hand. But, when the process becomes automatic and is a lens through which society views itself, it transcends the category of image and becomes something else — a gaze.

The Rotoscopic Gaze

A gaze is a mediating step in the looking process. It is a way of seeing that both informs and is informed by its subject. It implies active if unaware, participation of the gazer in creating the looked-upon image. Similar to the apparent truthiness of a photograph, gazes often feel natural and are therefore not immediately recognizable, especially to those subjected to them. This is the case when TikTok users, without knowing anything about rotoscoping, are rotoscoped by and rotoscope images through the filter and editing process. They not only produce rotoscopic images but also experience the world through the eye of the rotoscope, as a gaze.

The recursivity of a gaze imbues it with material consequences. Gazes do something. The rotoscopic gaze does to the physical world what the rotoscope does to a moving image, it separates subjects and produces movement data. Seeing the world with a rotoscopic eye is to see one that is traceable, trackable, mappable, modelable, and composite-able. Through this gaze, the rotoscope begins to resemble a technology of control, one that can create the world in its own image. If this sounds far-fetched, remember that the entirety of the App economy functions on the isolation of subjects for the purpose of data extraction understood now as Platform or Surveillance Capitalism. These same tech CEOs are the ones pushing new immersive technology like Facebook’s massive investment in augmented and virtual reality with its Meta Quest Pro headsets and its new mixed reality Presence Platform. The augmented (and data-extracted) experiences the new technologies promise are that of a fully integrated rotoscopic gaze. The user and their environment are tracked, isolated, and mapped with new images instantaneously.

It’s necessary to underscore that this gaze is emergent from 19th Century camera technology. The limitation of a purely photographic space became obvious in the first decades of its existence, as pointed out previously. Its early practitioners forged a new type of space, a layered space. This is implicit in the Muybridge/Marey motion studies and explicit in Georges Méliès films. The subject of the rotoscopic gaze becomes an intermediary between embellishment from above and compositing from below. The subject exists between layers only after it is freed from its photographic context by a rotoscopic process. This is perhaps the clearest in early cel animation techniques that relied on the combination of various media assets painted onto clear acetate sheets to compose its images. The development of Walt Disney’s multi-plane camera was perhaps the purest materialization of this way of thinking.

Thinking this layered space is the rotoscopic gaze. Knowing that to create any given piece of film or animation a number of layers must come together and therefore easily composite-able media assets must be created is the rotoscopic gaze. Implementing this gaze turns filmed subjects into decontextualized movement data. This data can be used to track, adorn, or erase its source. This was done through tedious analog processes throughout much of the 20th Century, but the introduction of digital cinema made it intrinsic to all media production. The teen making face-filtered TikTok videos of themselves superimposed onto a video is the same as the motion capture suit-wearing celebrity performing in front of a green screen who is the same as the actor on a sound stage fifty years before them.

It has been pointed out that the history of 20th Century film is the history of animation and visual effects at the service of creating the ‘reality effect’ of live-action film. Rather than concede to this point of view, one that favors realist film over all others, the rotoscopic view recognizes the necessity of layer space in the first place and the tools needed to support that space to create the film and media landscape of the last century and this one. Recognizing the dominance of this type of image in today's visual culture allows us to think rotoscopically.